Wetlands are the interface between land and water. The land itself need not be covered with water to make a wetland; all that is required is a high water table in the soil, high enough that the plants which grow there must have special adaptations to live under the wet conditions. Such plants are called hydrophilic, or water-loving, and are used to delineate wetlands. Another type of wetland, the mangrove swamp, is discussed here. This section will focus on several wetland types found in North America.

To the right and below are images of a cypress swamp. Contrary to popular use, a swamp is a wetland populated by trees, not grasses. Cypress trees grow over a wide portion of the southeastern United States; while mangroves grow in salt water, cypress trees grown in freshwater. Prized for their wood, which is highly resistant to decay, many of the cypress trees have been cut down, often for such "vital" tasks as providing long-lasting mulch. Destruction of cypress wetlands no doubt played a role in the destruction caused by hurricane Katrina in 2005; healthy cypress stands would have absorbed much of the impact of the storm.

Like black mangroves, cypress trees have pneumatophores, spongy wooden structures which extend from above the water down below the waterline to the roots. The pneumatophores (also called cypress knees) provide oxygen to the roots, which are growing in the anoxic, nutrient-rich sediments of the swamp.

Cypress Swamp, Florida

Pneumatophores

Cypress Swamp, Florida

Fakahatchee Strand, Florida

Dwarf Cypress, Everglades NP

Fakahatchee Strand, Florida

The Fakahatchee Strand in southern Florda (left) is another example of a Cypress Swamp, although here epiphytes are more in evidence.

In the everglades proper, small Dwarf Cypress communities are found; they grow in the dwarfed form because the underlying bedrock is too close to the surface for sufficient soil and nutrients to accumulate.

Below, Water Lettuce is a floating aquatic plant. There is some dispute as to whether or not it is native to Florida. What is not in dispute is its ability to cover small bodies of water.

Singer Lake Bog, Ohio

Singer Lake Bog, Ohio

Let's head back north to Ohio and to a unique ecosystem, the Singer Lake Bog. Northern bogs are formed as smalll kettlehole lakes (formed by a chunk of ice breaking off a retreating glacier; the ice forms a void in the glacial till and as it melts a lake is formed where the ice used to be). As the lakes age (eutrophication), they gradually fill in. One particular plant species, Sphagnum Moss has two rather unique abilities. One is to make the water more acid, the other is to hold extensive amounts of water. The acid waters of the bog slow decomposition, and floating mats of sphagnum and other plants - up to the size of small trees - develop on the lake. It is quite a thrill to walk on such a bog and see your footsteps transformed into rolling waves that shake trees 40 feet away. In the pictures above you can see some of the open areas of the bog, which in addition to the sphagnum contains a good deal of leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata); it is often called a Leatherleaf Bog for this reason. Much of the land around this bog was slated for development, at least until Jim Bissell of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History began working with landowners to preserve it. It is perhaps one of the best remaining remnants of such bogs left in Ohio; the others having been lost to development.

Many of these bogs have the floating mat surrounded by a "moat" of deeper water, hence access to the bog mat is often difficult unless a convenient tree has fallen to provide access (right).

Cleveland Museum of Natural History Website: http://www.cmnh.org/naturalareas/singer-lake.html

Singer Lake Bog, Ohio

Singer Lake Bog, Ohio

Singer Lake Bog, Ohio

Singer Lake Bog, Ohio

Singer Lake Bog, Ohio

Poison Sumac (Toxicodendron vernix)

Above left - a view of the mat and moat at Singer Lake Bog. Above right - another view of the edge of the bog. Left - Poison Sumac (Toxicodendron vernix). Poison sumac is rarely encountered outside of a bog. One naturalist had this description of how to identify it in the field:

"Walk across a bog mat until you lose your balance and begin to fall. The small tree you reach out for in order to steady yourself is Poison Sumac".

Below left - Sphagnum Moss (Sphagnum andersonianum). As mentioned above, one of the characteristics of this moss is to make the water very acidic. Under acidic conditions, few bacteria grow and decomposition stops. With no decomposition, nutrients, particularly nitrogen are in short supply. To counter this many bog plants have turned to carnivory to trap insects, which are rich in proteins (and thus nitrogen). The Sundew (Drosera sp.) is one example at Singer Lake Bog. Long hairs which exude a sticky sugary sap attract insects, which become entrapped and which are eventually digested.

Sphagnum Moss (Sphagnum andersonianum)

Sundew (Drosera sp.)

Pitcher Plant

Pitcher Plant Sarracenia purpurea - Maine

More carnivory at the bog. Pitcher Plants (above) have leaves folded and merged to form a large cavity which fills with water (the pitcher). Hairs on the inside surface of these leaves all point downward, making it difficult for insects to get out. Eventually they drown in the water, to which the plant adds digestive enzymes; their nutrients are then absorbed by the plant. Interestingly, some insects are unaffected by the figestive juices of the pitcher plant and complete their life cycles inside the pitcher.

The Pink Ladyslipper (Cypripedium acaule) (right) is not a carnivorous plant, but a colorful addition to many bog habitats.

Below - two views of bogs in northern Minnesota. The bog on the left still has a moat of open water as well as open water (and a beaver lodge) in the middle of the bog. The bog on the right has almost completely filled in.

Pink Ladyslipper (Cypripedium acaule) (Maine)

Bog - Minnesota

Bog - Minnesota

Maple Swamp - Ohio

Swamp Darner - Epiaeschna heros

Another form of wetland is the maple swamp, a habitat common on old lake terraces surrounding Lake Erie in Ohio. These poorly drained soils retain moisture in the spring, and water remains on the ground for extended periods in the summer. One inhabitant of this ecosystem is the dragonfly called the Swamp Darner (Epiaeschna heros). The females of this species lay their eggs on rotting logs in the water (right); the eggs will hatch when the water returns the next spring.

Swamp Darner - Epiaeschna heros

Swamp Darner - Epiaeschna heros

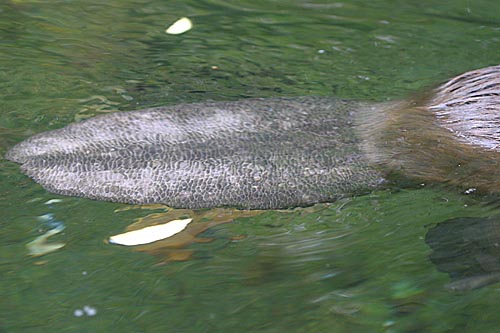

Beaver - Castor canadensis

Humans are not the only creatures whose dams create ponds and wetlands. Beaver ponds are interesting aquatic habitats in their own right; when the beavers abandon the dams and the ponds drain the wetland that remains is yet another important habitat for many species. Beavers build dams in order to flood ponds; they use the ponds to store their food - tree branches) and build their lodges, both protected from terrestrial predators. Once the beavers deplete the young trees (which are small enough to cut and which have nutritious bark), they abandon the site and move on. Wetland species such as Swamp Rose (Rosa palustris) may be found around the beaver pond or in the wetland formed after the beaver move on.

Beaver Lodge - Castor canadensis

Swamp Rose Rosa palustris

Jackson Bog Fen - Stark County, Ohio

Jackson Bog Fen - Stark County, Ohio

Jackson Bog Fen - Stark County, Ohio

Potentilla fruticosa Shrubby Cinquefoil

Jackson Bog Fen - Stark County, Ohio

Potentilla fruticosa Shrubby Cinquefoil

Jackson Bog Fen - Stark County, Ohio

Horsetail, Equisetum sp.

Horsetail, Equisetum sp.

Horsetail, Equisetum sp., is a primitive type of plant often found in wetlands. These plants have unique jointed stems (left) and leaves arranged in whorls at the joints. The reproductive structures of some species have long threadlike leaves (above) that resemble the tail of a horse (in texture if not by sight, at least to whoever named this stuff). The stems have a high concentration of silica; any horse that tried to eat them would soon have its teeth worn down. Settlers used to use the abrasive stalks to scour their pans, hence another common name, scouring rushes. Today settlers use brillo pads like everyone else.

Below - an example of a marsh in Ohio. Strictly speaking, a marsh is a wetland dominated by grasses, while a swamp is dominated by trees. You can see some dead trees in the picture at the lower left; in this case a change in water levels probably drowned some trees growing there during dryer times. Marshes are often critical habitat for waterfowl and a variety of other species.

Housing on Filled Wetlands, San Francisco

Killbuck Marsh, Ohio

Killbuck Marsh, Ohio

Two mammals of the marsh: The Muskrat (Ondatra

zibethicus), (above and right) is a herbivore which feeds on marsh

plants. They live in holes on the bank, or in abandoned beaver

lodges or piles of vegetation (below right) which the muskrats themselves

produce.

Two mammals of the marsh: The Muskrat (Ondatra

zibethicus), (above and right) is a herbivore which feeds on marsh

plants. They live in holes on the bank, or in abandoned beaver

lodges or piles of vegetation (below right) which the muskrats themselves

produce.

The Mink (Mustela vison), is a carnivore, a member of the weasel family, and a predator of muskrats. Basically, they kill the musrats, eat them, and take over their houses. It's like ethnic cleansing at your own local pond. The mink pictured here is not gripping some hapless muskrat, but one of its own young which it was moving from one den to another (no doubt stolen from some muskrat).

Mink (Mustela vison)

Mink (Mustela vison) with kit

In contrast, all the Cottonmouth Water Moccasin (Agkistrodon piscivorus)

can do to you is bite you, and in some cases, kill you.

They are venomous, being related to copperheads and rattlesnakes, and live

in wetlands of the southern United Snakes States.

All snakes are important in controlling rodent populations, and there really isn't any cause to kill any of them. Above all, if you are in a boat, don't empty your revolver into a snake which has fallen into the bottom of the boat. Dumb idea if you think about it.

OK. The snake at upper right is a water moccasin, the 3 pictures to the left are all northern water snakes, and the photo below is a water snake of some sort from Florida (note the vacant, beady, malevolent eyes).

Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

is an invasive wetland plant from Eurasia. With no native predators,

this plant forms dense stands which crowd out native plants such as cattails

(Typha sp., right). Although it's pretty to look at, the

loosestife does not have as much nutritional value for wildlife as do native

plants. Incredibly, while thousands of dollars are spent annualy on

loosestrife control, some garden centers still sell them as landscape

plants. Various insects species have been imported to help control

this pest.

Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

is an invasive wetland plant from Eurasia. With no native predators,

this plant forms dense stands which crowd out native plants such as cattails

(Typha sp., right). Although it's pretty to look at, the

loosestife does not have as much nutritional value for wildlife as do native

plants. Incredibly, while thousands of dollars are spent annualy on

loosestrife control, some garden centers still sell them as landscape

plants. Various insects species have been imported to help control

this pest.

Below: Many birds use wetlands and this web page doesn't do justice to them. One of the noticeable birds, however, is the Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) (below). The males have bright red shoulder epaulets which they use to warn rivals encroaching on their territories. These birds feed primarily on insects.

Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus)

Spotted Turtle - Clemmys guttata

Green heron - Butorides virescens

Some odds and ends from the wetland: With its heavy shell and unwebbed feet, the Spotted Turtle - Clemmys guttata (above) is an inhabitant of wetlands rather than open bodies of water. These carnivorous turtles are found in the northeastern United States and along the eastern coast; with the decimation of our wetlands the future of this species is in doubt.

The Green Heron is relatively common; the specimen here is perched on a muskrat mound and has just captured a tadpole.

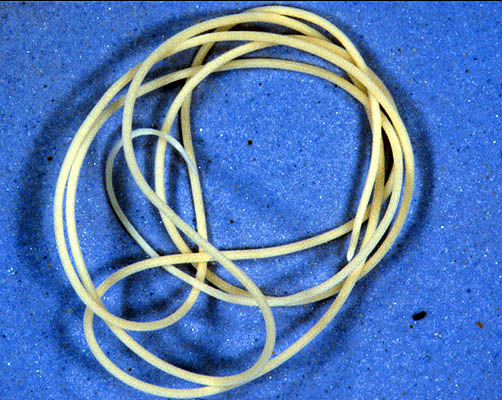

The horsehair worm (right) is disgusting or fascinating - depending on your point of view. Growing up as a parasite in an insect host, the worm modifies its host to cause it to seek out a puddle, into which the insect jumps. The adult worm then emerges into the water, where it mates and lay eggs. Another insect then consumes the eggs and the cycle begins anew. This manipulation of the behavior of a host by a parasite would be the fascinating part.

Spring peepers (below) are common in the northeastern United States in many wetlands. Their calls, heard mostly at night in the early spring, are one of the first signs of spring for many. The larvae develop into tadpoles before the water dries up (hopefully).

Cranefly larvae are found in streams (as this one, below right was) or in moist soils. Most are herbivorous.; they can be quite sizeable.

Horsehair Worm - Nematomorpha

Spring Peeper, Pseudacris crucifer

Cranefly Larva - Tipula sp.

Eastern Newt, Notophthalmus viridescens, Adult

Eastern Newt, Notophthalmus viridescens, Red Eft Stage

Eastern Newt, Notophthalmus viridescens, Red Eft Stage

Newts depend on fishless ponds in order to reproduce. Unfortunately, a lot of people think that a pond isn't a pond without fish. They toss in a few, and in a short time a pond full of diverse amphibians and insects becomes a pond full of stunted bluegills. Trust me folks, bluegills won't go extinct!

In any event, the Eastern Newt has an unusual life cycle for an amphibian. The adults are aquatic and mate and lay their eggs there. The eggs hatch into aquatic larvae with external gills. After a period of growth, the gills are resorbed and the larvae leave the water as a juvenile stage, the red eft (this is the unusual part). The red eft feeds on small invertebrates on the moist forest floor for a year or two before returning to the pond as an adult. Presumably, the bright red color of the eft is a sign to predators that the eft is poisonous; it may also have some camouflage value among the leaves of the forest floor.

Eastern Newt, Notophthalmus viridescens, Red Eft Stage

Wood Frogs, Rana sylvatica, in amplexus

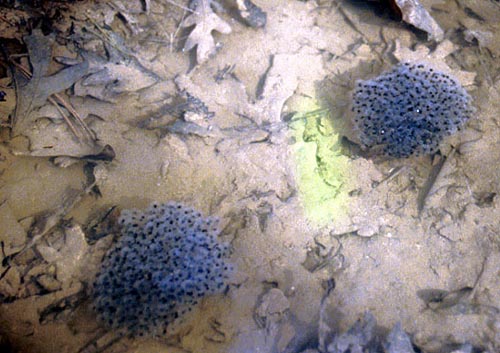

Above right - Wood Frogs are another early-breeding species in Ohio. Their bizarre, duck-like calls can be heard while there is still snow on the ground from a late-season snowstorm. Able to resist freezing temperatures, the adults overwinter on land, and emerge early to move to small temporary puddles (tire ruts on jeep trails are a favorite, if dangerous site). Here they mate (technically, the embrace of the female by the male is called amplexus rather than copulation because fertilization is external, not internal. The eggs are clumped and again hopefully complete development before the puddle dries up or another vehicle comes along.

Another wetland species is the Northern Leopard Frog, Rana pipiens (below). These small frogs are typically found in wet meadows; they require open water to breed, however. This species was a favorite for use in dissection laboratories.

Wood Frog eggs, Rana sylvatica

Northern Leopard Frog, Rana pipiens

Northern Leopard Frog, Rana pipiens

Young Cranberry Plants

Wetlands have a number of uses for humans; a number of commercially important products including cranberries (left), blueberries, rice, peat moss, fish, etc. are all farmed in wetlands.

Saw-grass (Cladium jamaicense), Everglades National Park

Alligator - (Alligator mississippiensis)

Saw-grass (Cladium jamaicense), Everglades National Park

Water flows through the saw grass in a very thin sheet; only at the wettest times of the year would there be standing water there.

The alligator is commonly thought of as the "typical" animal of the everglades, but it is restricted to the swamps and the more open water areas such as larger sloughs (see below).

Saw-grass (Cladium jamaicense), Everglades National Park

Slough - Everglades National Park

Burned Area - Everglades National Park

What is not appreciated by many is the importance of fire in the Everglades ecosystem. The importance of fire in a wetland ecosystem seems at first to be counterintuitive, but one the natural water cycle of the ecosystem is understood the value of fire becomes apparent. Under natural conditions, the everglades dry out during the dry winter season (except the deeper sloughs and alligator holes). Summer brings thunderstorms (right), and these storms bring lightning which starts fires in the dry saw grass. Trees and other woody vegetation caught in these fires dies (below); the sawgrass is able to quickly regrow as the thunderstorms also dump substantial water which again floods the everglades (below left).

Approaching Storm - Everglades National Park

Burned Area - Everglades National Park

Burned Area - Everglades National Park

Salt Marsh - Slough - Everglades National Park

Slough - Everglades National Park

Unfortunately, the natural water cycle has been greatly modified by human intervention. US highway 41 (and Interstate 75 to the north) cuts across the state and the everglades. The highway is built on fill dredged from an adjacent channel (below left). This alone has transformed the everglades, rather than a rive "miles wide and inches deep" it is now contained and channelized, with water controlled by structures such as the one shown in the figure below right. With these structures, the Army Corps of Engineers and the water control districts in southern Florida can control the movement of water in the everglades. Unfortunately, human needs (such as drinking water for greater Miami and irrigation needs of agriculture) often mean that the water is flowing during the dry season and preventing the fires.

Slough - Everglades National Park

US 41 across the Everglades

Water Structure - Florida Everglades

Sugar Cane Fields, Everglades Agricultural Area, near Lake Okeechobee

Burned Sugar Cane Fields, Everglades Agricultural Area, near

Lake Okeechobee

Vegetable Fields, Everglades Agricultural Area, near Lake Okeechobee

No agricultural crop has had as much impact on the glades as sugar cane. With the communist revolution in Cuba, the United States embargoed sugar from that country, and turned instead to domestic supplies from beets in Idaho, corn in the midwest, and sugar cane in Florida (the latter grown on swaths of the everglades by companies often controlled by Cuban exiles). Artificially raised prices (due to the embargo) and cheap water (courtesy of the Corp of Engineers) were the only things that made sugar cane agriculture profitable in south Florida, and powerful political interests have worked to keep it that way. Sugar cane fields are alternately burned and flooded (above) at various times of the year, to help recycle nutrients and control pests. The sugar cane is also extensively fertilized, and when this excess fertilizer flows off the land and into the everglades it has an extensive impact on not only the sawgrass ecosystem but other ecosystems downstream as well, including, ultimately, the coral reefs of the Florida Keys which can be overgrown by algae stimulated by the excess nutrients.

A portion of the everglades has been bought back from the sugar interests (your tax dollars at work; I'd just "forget" the funding for the Army Corps of Engineers to control the water in the area, myself) and converted into a "buffer zone" (below). In this area, plants such as cattails and others grow and remove a lot of the nutrients before they can get to the sawgrass exosystems - but remember that the buffer zone itself is taken from land that used to be sawgrass. This buffer zone helps to protect the other ecosystems but is a faint echo of the diversity found in the less impacted areas.

Everglades Buffer Zone

The figures to the right and below speak for themselves.

Finally, a quick look at the Bayous of Louisiana. This is basically a cypress swamp, although a bit less subtropical that the cypress swamps of southern Florida shown earlier. These wetlands lie along the Mississippi and along the coast; they serve many important functions, chief of which (from our perspective, at least) is absorbing floodwaters. During hurricane Katrina we found out to our dismay what happens when such natural ecosystems are reduced - their ability to absorb floodwaters and reduce storm surge is also reduced, and the effects of flooding are magnified.

In addition to the ability to absorb floodwaters, these wetlands absorb a huge amount of nutrients. Without the bayous, these nutrients would go straight into the Gulf of Mexico and increase the size of the "dead zone" that is now developing there. In this area the nutrients from the river stimulate huge blooms of phytoplankton. When the phytoplankton die and decompose the decomposers increase greatly in number. All of these decomposers use oxygen, and they eliminate oxygen from the surrounding waters, creating a "dead zone"

By themselves, of course, the bayous are are area very rich in wildlife of all types.

These 3 pictures courtesy of Quan Yuanfei (right), a 2007 graduate of Marietta College and now a graduate student at the University of Louisiana.