|

Mill Creek, Pennsylvania |

|

First-order stream - Montana |

First-order stream - Montana |

|

First-order

stream - Washington County, Ohio |

Headwater streams: The smallest permanent streams in an area

are called first-order, or headwater streams. In forested

areas, at least, these streams are often completely shaded, the streambed is

often blocked by fallen timbers, and the food webs are based on the huge

input of leaves and woody debris from the surrounding forests.

Gradients may be steep, and the streams may flood during snowmelt in the

spring (above). At other times of the year, however, the forest canopy

and porous soils of the forest floor absorb sudden downpours and flooding is

thus minimized. The intact forest also releases water to the stream

slowly and steadily, so that flow is maintained even during short dry

periods. The invertebrate fauna is usually dominated by shredders,

organisms capable of feeding on the decaying leaves and woody debris.

In-stream production by algae is minimized due to the forest cover, although

in deciduous forests there may be such production in the spring before the

trees leaf out (see the picture to the left and the picture below).

Fish may well be absent; their role as predators taken over by salamanders

and some insect species.

|

|

First-order

Stream , Broughton Nature Preserve, Washington County, Ohio |

Junction of two First-order

streams (Jackson and Irish Runs) to form a second-order stream (Archer

Fork), Washington County, Ohio. |

|

Avalanche

Lake, Glacier National Park, Montana |

Avalanche Creek, Glacier National

Park, Montana |

|

Some mountain streams: These Montana streams are bigger than

headwater streams and begin to show some intermediate characteristics.

The surrounding forest is no longer as dominant, and as a result in-stream

production by algae is relatively more important than it is in

headwater streams. Aquatic insect communities now contain larger

numbers of grazers and filterers than were present in the

headwater streams. Snowmelt from adjacent alpine areas causes

significant flow in these streams, often for much of the summer. If

there has been a fire or clearcut in the watershed, the soil may erode

during these flooding events (see the picture of MacDonald Creek

below). Fish are common in most reaches of these streams, except those

above particularly high waterfalls.

For more on the

feeding strategies of aquatic organisms, particularly aquatic insects, look

here.

|

Avalanche Creek, Glacier National

Park, Montana |

|

Bear Creek, Montana |

MacDonald Creek, Glacier

National Park, Montana |

|

MacDonald Creek, Glacier

National Park, Montana |

|

Battenkill River, Vermont. |

Tuolumne

Creek, Yosemite National Park |

|

Little

Muskingum River, Dart, Ohio |

Higher-order streams: As streams

become even larger, moving beyond first and second order to 3rd and 4th

order, the forest canopy falls away and the stream is exposed to more

direct light. Grazers and scrapers become even more important at the

expense of shredders. Often these reaches of a stream my have the

greatest diversity. Note the clarity of the Battenkill River,

which supports extensive trout fishing. The water is about 1 meter

deep in the pool where the rocks on the bottom can be seen clearly.

People in Vermont have made a decision to protect the clarity of the

waters - and thus the tourist economy - by practical measures such as

restricting animal access to streams, not plowing to the edges of the

streams, restricting ATV's in streams, etc. The Little Muskingum

River, to the left, is the largest river in Ohio not affected by a

major city. The water is turbid as a result of unrestricted ATV use,

poor farming practices (including allowing cattle unfenced access to

tributary streams), poor construction practices, poor road-maintenance

practices, poor oil-and-gas well maintenance practices and the like.

Citizens in this watershed have resisted all attempts to help them come up

with their own solutions to these problems, and have resisted expansion of

the Wayne National Forest in the area. The local school

system is in desperate need of funding; rather than turning to

tourism as a possible solution the locals hold out for someone to come in

and turn the hills into a giant shopping mall or some other

revenue-generating operation. Recent history suggests that further

closings of industrial operations along the nearby Ohio River are more

likely than any great miracle of industrial/commercial activity. The Brule

River also supports healthy tourism/fishing; and the Tippecanoe

River runs clear despite flowing through some of the most intensely

farmed (and intensly conservative) land in the country. Isn't it

time to put conservation back into conservatism?

Soapbox ends .... now. |

Brule River, Wisconsin

|

Tippecanoe River, Carroll County Indiana.

|

Little Muskingum River, Washington County, Ohio

|

White River, Indianapolis, Indiana

|

|

Monitoring Water Quality: One of the best

ways to monitor water quality is to directly monitor the benthic

macroinvertebrates (insects and other invertebrates that live on the

bottom of the stream). They are in the water 24/7, and unlike fish,

can't swim away during an episode of pollution. As a result, they

integrate and record water quality over the recent past. Also, it is

less expensive to monitor such populations than it is to run the large

number of chemical tests that would otherwise be required. The Ohio

EPA has led the nation in developing methods and standards for the use

of benthic macroinvertebrates (and other organisms) to monitor water

quality.

Above: Kick screens and Surber samplers

(left and right) are used to obtain qualitative (kick screen) and quantitative

(Surber sampler) samples of benthic macroinvertebrates.

Left: benthic macroinvertebrates in a sampling pan.

Top - a large stonefly nymph (Acroneuria sp.) dominates this

sample. A pair of amphipods is right in front of the

stonefly, the posterior of a dragonfly is visible, as is a smaller

stonefly. Bottom: a long slender damselfly larva (Calopteryx

maculata) is flanked by a pair of mayfly nymphs (Heptageniidae).

A water penny (Psephenus herricki) is on the bottom of the

pan under the damselfly. All of the organisms in these two

photographs are generally indicative of moderate to very good water

quality. Below right: A midge larva (Chironomidae).

The red color is caused by the presence of hemoglobin, which in turn

allows these larvae to exist in water with very low oxygen levels.

Presence of these larvae in large numbers is indicative of organic

pollution and attendant low dissolved oxygen. Worm-like organisms

are also better at living on silt-covered bottoms in streams affected by soil

erosion, the number one water pollution problem in the United

States today.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Benthic Macroinvertebrates, continued:

upper left - Corydalus sp., also known as a hellgrammite.

Hellgrammites are predators found in streams throughout the midwest.

Above right: A caddisfly larva. Caddisflies often build

cases from materials in their environment, here sand grains and twigs held

together by silk spun by the caddisflies. The case serves as mobile

protection while the caddisfly scrapes food from the rocks (or in other

species, while it shreds fallen leaves); the heavy materials in the case

also serve as ballast in strong currents. Left: Ephemerella

needhami, a mayfly larva living and feeding on Cladophora,

a filamentous algae often found in streams. Below left: a

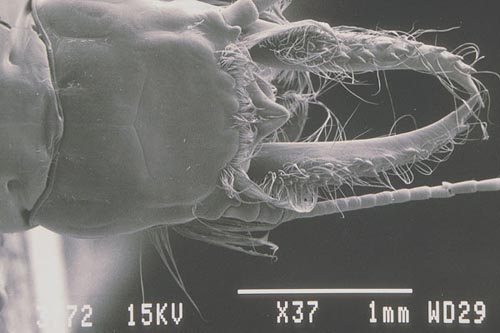

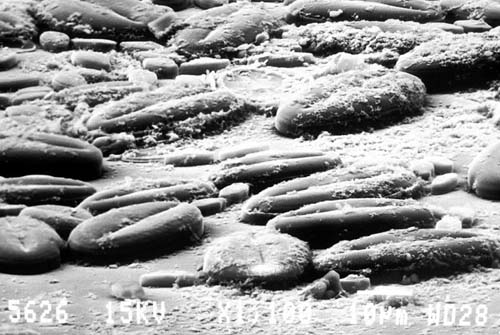

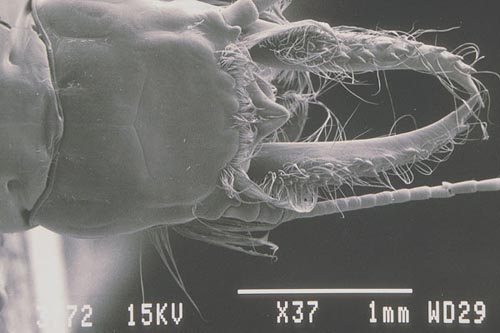

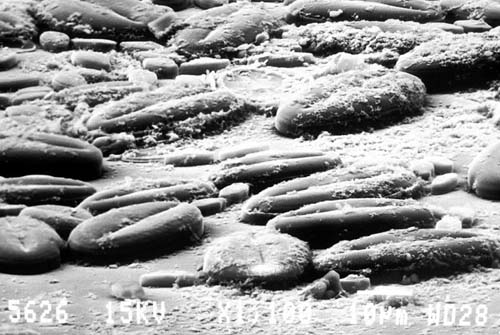

scanning electron micrograph of Ephoron sp., a mayfly larvae

which burrows into the sediments of rivers. Below - Hydropsyche

sp., a caddisfly which does not build a case but rather spins a catchnet

of silk which it uses to filter food material from the water.

All of these insects are generally indicators of good water quality. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

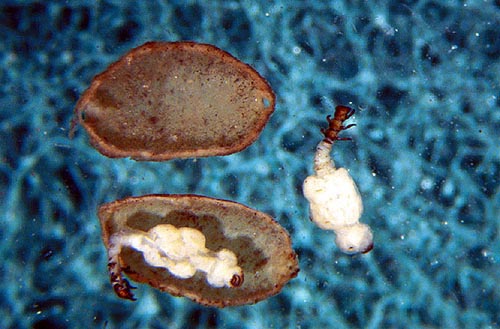

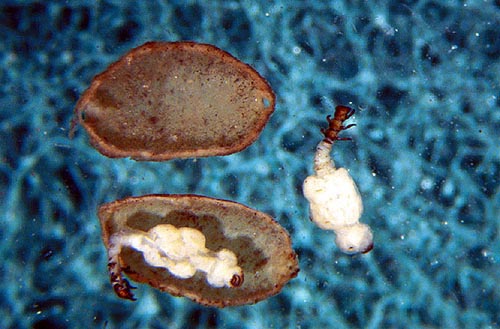

Still more benthic invertebrates: Above left, larvae of water

scavenger beetles, family Hydrophilidae. These beetles are

predators. Above, snailcase-making caddisflies, Helicopsyche

sp. which spin silk which they use to bind sand grains into cases which

resemble snail shells. These are tiny, only a few mm

across. Another tiny caddisfly is the purse-case making caddisfly

(Hydroptilidae), left. Here the case is almost completely silk,

containing a strangely shaped larva within. Below, two more species of

mayflies. On the left, Isonychia bicolor, a streamlined larva

which can be mistaken for a small bottom dwelling fish like a darter. Isonychia

filters food from the water using long hairs on its front legs. On the

right, below, is Apotamanthus sp., which uses its fierce-looking

mandibles as levers to move small rocks so that the larva can move under

them and filter or deposit feed. All of these species tend to be

found in clean water.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Above left: A water penny beetle

larva, Psephenus herricki. These flattened larvae can

crawl under rocks to hide; when out on the rock surface scraping off algae

they modify the flow of water around them making it easier for them to

stay in place and harder for fish to remove them. They do not do this by

suction as has been long suspected; but rather by gripping the rocks tightly

with their legs. They cannot hold onto a smooth glass surface, and

individuals with holes in their carapace (thus unable to produce suction)

are able to hold on perfectly well. All this and more in: McShaffrey,

D. and W.P. McCafferty. 1987. The behavior and form of Psephenus

herricki (DeKay) (Coleoptera: Psephenidae) in relation to water flow. Freshwater

Biology. 18:319-324.

Above right - a filter-feeding blackfly

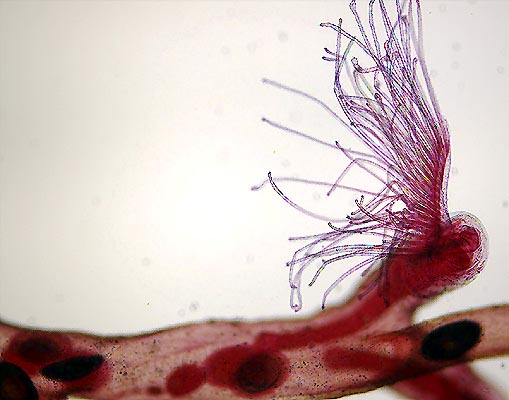

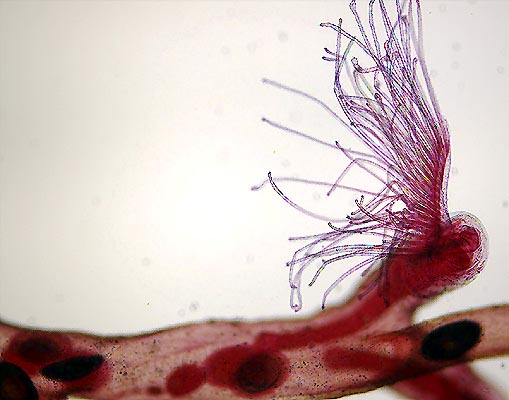

larva (Simuliidae). Left: a colony of Bryozoa growing on a

rock. Somewhat coral-like, bryozoans are colonial filter

feeders. The two photos below show Obelia (left) and Plumatella

(right) in images made from stained microscopic mounts. In the

image of Obelia you can see the individual zooids  with

their filter-feeding tentacles as well as several reproductive

structures. The Plumatella below shows one zooid and

part of the colonial stalk. Some freshwater Bryozoa can form colonies

25 meters long and about 1-2 feet in diameter. with

their filter-feeding tentacles as well as several reproductive

structures. The Plumatella below shows one zooid and

part of the colonial stalk. Some freshwater Bryozoa can form colonies

25 meters long and about 1-2 feet in diameter.

The inset picture is of a statocyst,

a bryozoan reproductive structure used by freshwater species; over the

winter cells of the bryozoan survive in this tough shell and sprout a new

colonly the following spring. The hooks help it keep in place on the

stream bottom. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Arctic to Tropical: 3 images of streams in the Arctic tundra

of Alaska (note the Alaska pipeline in the background of the image at

upper left). These streams may only flow openly for a few weeks each

year as they drain the melting snow from the surrounding tundra. There

may well be considerable production taking place in the streams themselves

as there is obviously little shading and less obviously 24 hours of sunlight

in the brief summer. Photos courtesy of Sarah Beck (MC 2001).

Sarah spent a summer on a REU project (Research Experience

for Undergraduates) run by Woods Hole studying

production in tundra streams.

Below: subtropical rivers in Florida. Both

images are of Rock Spring Creek north of Orlando.

Like many southern "blackwater" rivers; this stream is low

gradient and has the water discolored by tannins leached from the

leaves of plants overhanging the stream.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fish, Part 1. Fish, of course, are a major component of most

stream and river ecosystems. Here we will look at some of the smaller, less

well-known fish. Above: electrofishing is an effective

way to study fish populations. An electrical current generated on the

boat is introduced to the water with the long nets or with a boom sticking

out from the boat. Fish in the water are stunned and dipped out of the

water. Once caught, they can be identified, measured and returned to

the river. Smaller electrofishing units can fir in a backpack fro

smaller streams (wearing waders is definately a good idea). Right: a

small darter, a bottom dwelling insectivorous fish. Below

right: a Bluntnose Minnow, Pimephales notatus, below, an Emerald

Shiner, Notropis atherinoides atherinoides. Both were

caught in tributarieds of the Little Muskingum River in Washington County,

Ohio. Both feed on aquatic insects and smaller fish.

|

|

|

Emerald Shiner, Notropis atherinoides

atherinoides

|

Bluntnose Minnow, Pimephales notatus |

|

Northern Hog Sucker (Hypentelium nigricans) |

Johnny Darter (Etheostoma

nigrum) |

|

Rainbow Darter (Etheostoma caeruleum)

|

More fish from smaller southern Ohio streams:

The Northern Hog Sucker and the Stoneroller are both bottom dwellers,

the hog sucker feeds on insects while the stoneroller feeds on attached

algae. The two darter species are both insectivorous and

require clean streams with gravel or sand bottoms. The rainbow

darter is a male in its breeding coloration. The Redbelly Dace

also feeds near the bottom, but does not rest on it; it eats aquatic

vegetation and algae.

You can read more about various fish species here:

http://www.ohiodnr.com/wildlife/Fishing/aquanotes-fishid/fishtips.htm |

Southern Redbelly

Dace (Phoxinus

erythrogaster)

|

Stoneroller (Campostoma

anomalum)

|

|

Scud (Amphipoda)

|

Assellus sp. (Isopoda)

|

| Scuds (order Amphipoda) and Assellus

sp. (order Isopoda) are small crustaceans common in streams,

particularly small streams where they are both often associated with leaf

packs. Both are shredders, and feed on leaves and other such

organic material placed into a lake. Mussels feed at the

smaller end of the food chain; they filter tiny bits of material out of

the water. Some of this can be in the form of algae or other

plankton; other food for the mussels may be so-called fine-particulate

organic matter (FPOM, 250-1000 micron particles). North America

is the world center of mussel diversity, and small areas below century-old

dams on the Muskingum River in Ohio are among some of the most

diverse mussel beds left, with a high proportion of federally listed

endangered species contained in these relatively small areas.

Individual mussels can live for over 50 years. For more on mussels

see:

http://www.marietta.edu/~biol/mussels/1stpg.html

|

Mussel

|

|

Mussel bed at Devola, Muskingum

River

|

Mussel

|

Mussel bed at Devola, Muskingum River |

|

Crayfish are small crustaceans

that occupy many streams and rivers in North America and other parts of

the world. They resemble their saltwater cousins the lobsters (and

are also tasty, but it takes a lot to make a meal). Many live under

rocks in rivers and streams, others burrow into the banks of

streams, rivers, ponds, ditches, wetlands and the like. Often these

burrows will extend from the surface down to the water table; the upper

entrance of the burrow may be surrounded by a "chimney" of

excavated dirt. Other organisms, including a federally endangered

dragonfly larva, live in crayfish burrows. |

|

|

Industrial

waterway, Newark, New Jersey |

Acid Mine Drainage, Ohio

|

|

Seine River, Paris (as seen from

the Eiffel Tower) |

Water pollution affects streams and rivers of all sizes. In

eastern Ohio and other places where coal mining has occurred,

minerals from underground can become oxidized at the surface and in the

process give off acids that lower the pH of streams and lead to acid mine

drainage, which can have a detrimental effect on stream life. The

pH of the pictured stream was about 1, and the water sample had to be

diluted 10,000x before iron levels could be measured. Many cities are

built near water, and the industrial activities that take place on the

waterways pose the risk of contamination (Newark, above left); often

the nature of the stream is completely changed as a result of engineering on

the banks (Paris, left). Coal plants are often built on

rivers both for convenience in obtaining cooling water and for low cost of

coal transportation. Beyond the footprint of the plant itself,

however, there are a number of ecological ramifications that spread to the

surrounding countryside. Powerlines cut swaths through forests,

coal mines impact the land and streams, landfills are used to bury fly ash,

and of course the long-distance impacts of global warming and acid

rain. Warm water added to streams affects stream life in several ways;

for one, warm water holds less oxygen and organisms in warm water respire

more (and thus require more oxygen).

|

|

Power Plant at Brilliant, Ohio on

the Ohio River

|

Debris on the Ohio River |

|

Bonneville Dam, Columbia River |

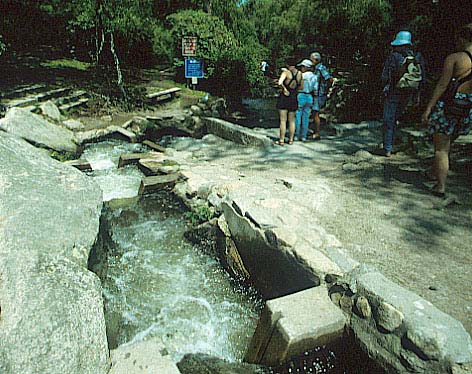

Fish

Ladder, Bonneville Dam |

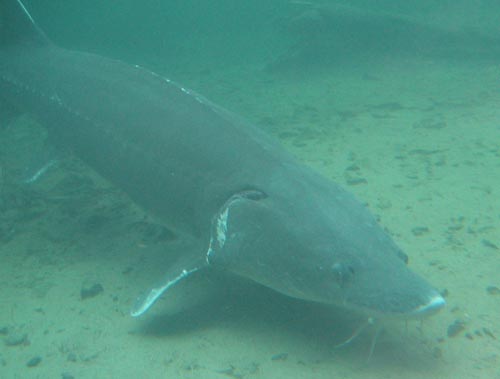

Dams are built on streams for many

reasons - to hold water for irrigation and drinking, to generate power, to

create lakes for recreation, to mitigate floods, and for navigation.

The Bonneville Dam on the Columbia River (above) generates

power and provides for navigation. One big problem with dams is that

they block fish from moving upstream. Many fish are anadromous;

they live in the ocean and return upstream to spawn. In the

northwest, salmon are a conspicuous and important anadromous

species. To allow salmon to bypass the dams, most are provided with

fish ladders (right). This allows fish like the Rainbow Trout

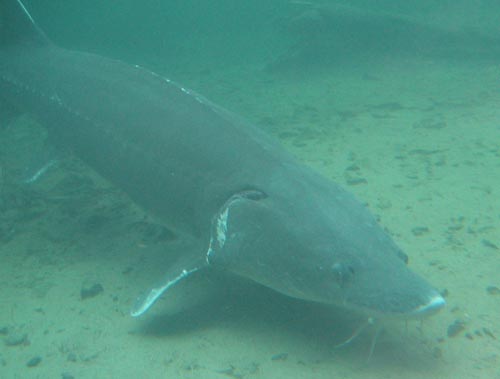

(Oncorhynchus mykiss) and the White Sturgeon (Acipenser

transmontanus) (below) to make it upstream to spawn.

Unfortunately, it also allows fish like the sea lamprey (below,

below right) to reach its spawning grounds; in the Great Lakes, completion

of the Welland Ship Canal from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario in 1829

allowed the lampreys access to the upper Great Lakes. Sea Lampreys

contributed to the decline of many commercially important fish species in

the Great Lakes as they feed by latching onto the sides of such fish.

Another problem dams cause fish is on the downstream side.

Juvenile salmon are ground up in the turbines (left) which power

the generators; in addition the water downstream from the dam is so frothy

that fish (and even human swimmers) cannot stay afloat. To get

around this, the Army Corps of Engineers actually rounds up the juvenile

fish and barges them downstream (really - see the picture below) |

Fish Ladder, Bonneville Dam |

|

Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) |

White Sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus) |

|

Juvenile

Fish Transportation Barge, Columbia River |

|

|

Banana processing plant, Costa

Rica |

To avoid pollution coming from

its banana processing plant at Finca Zurqui in Costa Rica, Dole Fruit

Company installed a small water treatment plant. I'm not sure this

mitigates all the chemicals sprayed on the field, but it's a nice gesture. |

|

Water

Treatment Plant, Costa Rica |

Yosemite Falls, Yosemite National Park,

California

|

|

Ohio and Erie Canal, Canal Fulton,

Ohio |

Ohio and Erie Canal, Lock 4, Canal Fulton, Ohio

|

| Streams and rivers have long been used for

transport, recreation, and sources of food. The Ohio and Erie

Canal in Ohio is but one of the many canal systems built in the United

States before the era of rail and road. Canoeing and kayaking

are popular recreational activities today; in the past these were the

preferred means of transport and exploration. The Ohio River is

still a major transport route; its tributary, the Muskingum River is still

canalized, with a system of dams that today are only historical in

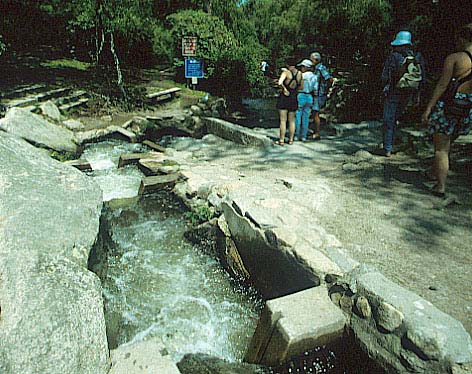

nature. Stony Brook on Cape Cod was extensively modified to

power a nearby grist mill - and for herring fishing. When the

herring made their annual run, residents could scoop them easily out of

this modified streambed.

|

Canoeing, Wekiva River, Florida |

Stony Brook, Cape Cod

|

Coal Transport and Crew - Ohio River and

Muskingum River, Marietta, Ohio

|

Diatoms (Cocconeis and Navicula

sp.)

|

Cladophora growing in a stream.

|

Diatoms (Cocconeis and Navicula

sp.)

|

Top and Bottom of the food chain in streams. Diatoms

(Scanning Electron Micrographs, left) are small algae with shell of silica.

Free-living in the water, or attached to the substrate as these are,

diatoms are a major food source for organisms in streams. Attached

diatoms are removed by scrapers among the herbivores. Cladophora

(above) is a filamentous algae that grows in streams.

Below, otters are small carnivorous mammals that

are often the top predators in streams. Feeding at will on mussels,

fish, turtles, frogs, etc., otters are also known for their playful

antics. River Otters released in Ohio to help the species recover

from extirpation due to trapping have been known to leave the streams and

wander inland for miles to raid fish farms. |

Otter at a zoo.

|

River Otter (Lutra canadensis), Lake

Eloise, Florida.

|

|

Caņo

Negro, Costa Rica |

Rio Puerto Viejo, La Selva Costa Rica

|

|

Tropical Rivers: Caņo Negro, above, is

crowded with tropical wildlife - and the tourists which come to see the

wildlife. Low-gradient tropical rivers (the Amazon and its

tributaries being the prime examples) are still important transportation

routes.

In 2005, we were privileged to stay for several days on

the Rio Puerto Viejo at the La Selva Biological Station.

This river is a good example of a mid-sized tropical river. These

rivers - whether headwater streams (right) or Rio Puerto Viejo itself -

are similar to temperate streams in terms of the relative importance of

in-stream vs. out of stream production and other factors. On the

other hand, tropical rainforest streams receive a constant flow of leaves

over the course of the year, and the canopy never opens up (in the

springtime) to allow algae to thrive in the streams.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Monteverde Cloud Forest |

Headwaters to mid-sized streams:

Headwater streams in the tropics also resemble their temperate

counterparts in many ways. One important difference, however, is the fact

that the rainfall (at least in rainforests) may be much more constant over

the course of the year, and at least in Costa Rica there is no snowmelt to

speak of!

Larger streams may show watercourses more indicative of differences

between rainy and dry seasons. This river in Costa Rica (below,

right) is shown just at the beginning of the rainy season. |

|

Monteverde Cloud Forest |

River, Costa Rica |

|

Rainy season - Rio Grande

de Tarcoles |

Rainy season - Rio Grande

de Tarcoles |

| At the beginning of the rainy season, the Rio

Grande de Tarcoles (above) is just beginning to swell. These

pictures, taken near the mouth of the river on the Pacific Coast, show the

river bearing silt from upstream.

To the right and below are small streams in the Rincon de la Vieja

National Park in Costa Rica. This is montane rain forest rather

than lowland rainforest. The ground is volcanic, as the park is on

the slope of a volcano. These steep gradient streams flow clear down

the hillside.. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

More views of small streams in Rincon de

la Vieja National Park, Costa Rica. |

|

|

|

|

Freshwater Crab, Monteverde Cloud

Forest, Costa Rica |

Longtail Salamander, Eurycea longicaudata |

| Above - One of the most conspicuous differences

in streams between the tropics and the midwestern United States is the

presence of crabs in the streams in the tropics.

Right - Longtail Salamander, Eurycea longicaudata, a

beautiful salamander found in streams in eastern Ohio. Salamanders

often play the role of top predators, particularly in small streams

without fish. Below right, the mudpuppy, Necturus maculosus

maculosus is a neotanous (retains its gills throughout life)

salamander that lives its whole life in water.

Below - the Muskingum River at Stockport, Ohio. This dam,

built in the 1800's, persists today. You can see the hand-operated

navigation lock on the far bank; the near bank holds a mill and has

variously seen service as a restaurant and bed and breakfast, and the

turbines have recently been used to generate electricity.

|

Longtail Salamander, Eurycea longicaudata |

|

Muskingum River at Stockport, Ohio |

Mudpuppy, Necturus maculosus maculosus |

|

|

|

|

|

Floods are part of living near any river.

This unusual summer flood hit Marietta in September 2004 as the remnants

of a 3rd hurricane in a two-week period (Charley, Frances, Ivan) reached

the Ohio Valley with significant rain. These pictures are of the

flood on the Marietta College Campus; the school was closed for a

week while student, faculty and staff volunteers cleaned and rebuilt the 3

dorms which were flooded. Floods like this normally hit Marietta in

the winter. The Army Corps of Engineers and the Muskingum Watershed

Conservancy district operate a number of flood control structures upstream

to minimize floods; ironically the navigation dams on the Ohio River that

keep the river level high enough for barges probably contribute to the

flooding Marietta now gets.

Below - in Costa Rica, even a small flood can have some real

consequences. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Marietta College has

an exchange program with Seoul Women's University in Korea.

As a part of this exchange, students from both colleges have studied their

local streams and compared results over the internet with their colleagues

at the other institution. Above left - a Marietta College team

studying Baker Run. Above right :

map of the Kapyong Creek site in Korea. Left - Korean

students sampling in Kapyong Creek. Below: Kapyong Creek and Korean

Mayfly. :

map of the Kapyong Creek site in Korea. Left - Korean

students sampling in Kapyong Creek. Below: Kapyong Creek and Korean

Mayfly.

Web site for the project:

http://www.marietta.edu/~biol/Korea/

|

|

|

|

|

MacDonald Creek, Glacier National

Park, Montana |

Snake River, Wyoming

|

|

Yosemite

Falls, a barrier to upstream migration of fish. |

Some pretty pictures to finish

this section out. |

|

|

|

| If you

haven't seen the section on lakes yet, perhaps this is a good time to go

there. |

with

their filter-feeding tentacles as well as several reproductive

structures. The Plumatella below shows one zooid and

part of the colonial stalk. Some freshwater Bryozoa can form colonies

25 meters long and about 1-2 feet in diameter.

with

their filter-feeding tentacles as well as several reproductive

structures. The Plumatella below shows one zooid and

part of the colonial stalk. Some freshwater Bryozoa can form colonies

25 meters long and about 1-2 feet in diameter.

:

map of the Kapyong Creek site in Korea. Left - Korean

students sampling in Kapyong Creek. Below: Kapyong Creek and Korean

Mayfly.

:

map of the Kapyong Creek site in Korea. Left - Korean

students sampling in Kapyong Creek. Below: Kapyong Creek and Korean

Mayfly.